Thousands of miles from her war-torn, splintered homeland, Mira Adanja Polak paused to ponder her recent glimpse of small-town America.

“This is a hidden part of America, where you get the feeling that people are not so rushed,” she said, waving a hand around a sun-soaked Courtyard on the campus of Slippery Rock University. “You still can get a feeling it’s like home, some of the cuisine, some of the tradition. People are not obsessed with getting rich.”

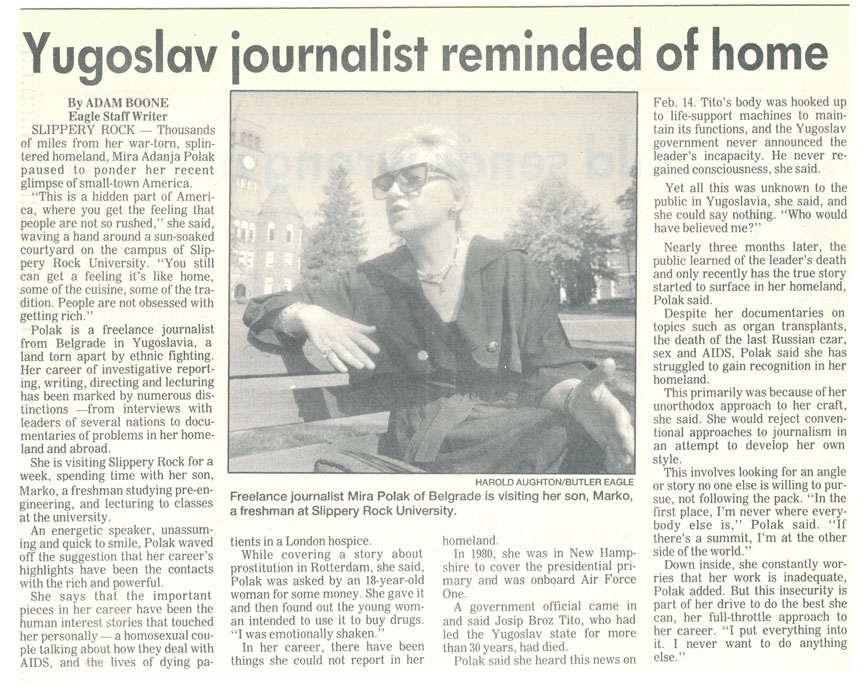

Polak is a freelance journalist from Belgrade in Yugoslavia, a land torn apart by ethnic fighting. Her career of investigative reporting, writing, directing and lecturing has been marked by numerous distinctions — from interviews with leaders of several nations to documentaries of problems in her homeland and abroad.

She is visiting Slippery Rock for a week, spending time with her son, Marko, a freshman studying pre-engineering, and lecturing to classes at the university.

An energetic speaker, unassuming and quick to smile, Polak waved off the suggestion that her career’s highlights have been the contacts with the rich and powerful.

She says that the important pieces in her career have been the human interest stories that touched her personally — a homosexual couple talking about how they deal with AIDS, and the lives of dying patients in a London hospice.

While covering a story about prostitution in Rotterdam, she said, Polak was asked by an 18-year-old woman for some money. She gave it and then found out the young woman intended to use it to buy drugs. “I was emotionally shaken.”

In her career, there have been things she could not report in her homeland.

In 1980, she was in New Hampshire to cover the presidential primary and was onboard Air Force One.

A government official came in and said Josip Broz Tito, who had led the Yugoslav state for more than 30 years, had died.

Polak said she heard this news on Feb. 14. Tito’s body was hooked up to life-support machines to maintain its functions, and the Yugoslav government never announced the leader’s incapacity. He never regained consciousness, she said.

Yet all this was unknown to the public in Yugoslavia, she said, and she could say nothing. “Who would have believed me?”

Nearly three months later, the public learned of the leader’s death and only recently has the true story started to surface in her homeland, Polak said.

Despite her documentaries on topics such as organ transplants, the death of the last Russian czar, sex and AIDS, Polak said she has struggled to gain recognition in her homeland.

This primarily was because of her unorthodox approach to her craft, she said. She would reject conventional approaches to journalism in an attempt to develop her own style.

This involves looking for an angle or story no one else is willing to pursue, not following the pack. “In the first place, I’m never where everybody else is,” Polak said. “If there’s a summit, I’m at the other side of the world.”

Down inside, she constantly worries that her work is inadequate, Polak added. But this insecurity is part of her drive to do the best she can, her full-throttle approach to her career. “I put everything into it. I never want to do anything else.”

(Adam Boone, “Butler Eagle”, 19 February 1992)

Lakše ćete pratiti šta radim i emisije koje želite da pogledate ako preuzmete aplikaciju za Android i iPhone.